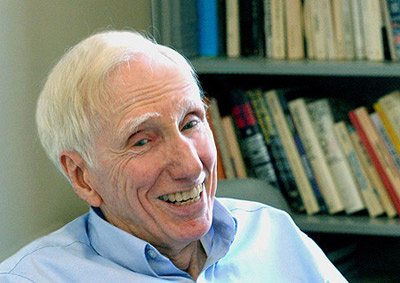

A Short Essay in Memory of Robert N. Bellah (1927-2013) by Richard L. Wood

In remembering Robert N. Bellah, I hope to evoke both the man and his intellectual work. So I offer here three ideas from Bob Bellah’s work that have made a difference in lives and intellectual trajectories, my own and others’, interspersed with two memories of my interactions with the man.

First, a bit of background: Following my undergraduate studies, I spent four years as a solidarity activist in Mexico and Central America. This was during the guerrilla insurgencies and civil wars of the 1980s, and I worked leading norteamericanos on trips in the region, striving to help them learn a bit about the real nature of our country’s allies there. In those years, when American involvement too often coddled human rights violators and brutal regimes, I gradually became alienated from large parts of American culture.

In 1987, as I prepared to return to the United States, a study participant gave me a copy of what was to me an obscure new book titled Habits of the Hearts. For the first time, I encountered a penetrating analysis that balanced what has gone awry in American culture with real understanding of the deep and abiding strengths of our culture – and how those strengths might yet produce democratic reform of American institutions. Along with its sequel The Good Society (also co-authored by Bellah with Richard Madsen, Bill Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steve Tipton), Habits became a touchstone for constructive engagement with our society – and also drew me into sociology as a discipline linking analytic thought, empirically grounded research on society, and the role of the intellectual in societal reform (via what Bellah termed ‘public philosophy’, akin to what we now call ‘public sociology’).

The first memory: As is the way of things human, constructive engagement with society may lead a young man to love. One day in 1989, as I courted Dana Bell, a fellow student in a course on Bellah’s work at the Graduate Theological Union (whom I subsequently married, surely to her everlasting consternation), Dana and I were hiking amidst the eucalyptus trees, berry bushes, and redwoods of the Berkeley Hills. Well, not exactly hiking at that moment, but rather enjoying one another’s presence. Dana looked past me, saying “Isn’t that Robert Bellah running up the trail?” I turned around to see the whitest ghost of a man I had ever seen, running on stick-thin pale legs. He said not a word to the young sweethearts, just looked and ran by us with a scowl on his face. Or maybe that was a smile; it was sometimes hard to tell with Bob Bellah. Whatever it was, it was not a puritanical, anti-pleasure scowl: As anyone who knew Melanie Bellah, Bob’s wife of many decades, will attest: Bob certainly embraced a fully embodied love – no Puritan anti-body theology at work there.

The second dimension of Bellah’s thought that influenced me strongly came in his early essays in Beyond Belief and Emile Durkheim on Morality and Society, which revolve around Bellah’s interpretation of the later Durkheim; especially important is his theoretical insight organized under the concept of “symbolic realism”. Bellah used that concept to interrogate how both religionists and secularists tend to think about the nature of religious truth claims. Symbolic realism suggests that to focus on the cognitive “truth” of religious symbols, narratives, rituals, and teachings is to ask a blindly literalist question on the wrong terrain. Rather, the richer question to ask is whether those symbols, narratives, rituals, and teachings “get at” something that is real in human society and personal experience – a distinction popularized by Karen Armstrong using the categories of logos and mythos. That is, we only understand religious experience – and the power of faith in the lives of persons and human collectivities – if we probe how religions connect people to dimensions of reality that transcend the taken-for-granted quality of everyday experience. Thus, in this view the religious faith that can provide the basis for responsible adult life in modern and post-modern conditions involves less a focus on “belief” in some other life, and more a focus on embracing those dimensions of experience that indwell and transcend the immediately apparent reality of things. The nature of such experience, as well as the symbols used to interpret it, remain fully open to critical analysis. But they cannot be falsified simply by mocking the cognitive truth claims of religious systems, typically developed under pre-modern conditions and expressed in categories incommensurate with modern and post-modern thought. The symbolic realist approach has allowed me, and I am sure many others, to stay true to the deepest insights of my own spiritual and political experiences, while also staying committed to the vocation of a critical intellectual.

The second memory: In 1989, I started doctoral studies in the Department of Sociology at Berkeley, having enrolled there to study with Bellah. At my first meeting with that rather severe apparition from the Berkeley Hills, I tried to explain my interests in sociology. He was sitting across the desk, apparently scowling again, looking down and away as I spoke about my interests (no doubt none too articulately). He made no eye contact, and so in the insecurity of first-year doctoral studies I was left thinking ‘this is awful, I’m coming off as a gibbering idiot’. But then he asked an insightful, probing question, precisely on my point – he had been listening intensely, hearing every word, and spent the next half hour seeking to understand my mind. That was the beginning of a long and generous mentorship, and that was Bellah: he took ideas utterly seriously – his own and others’. He insisted that ideas are the single most important thing in the world.

The third dimension of Bellah’s thought that will continue to be crucial in the years ahead only came to full fruition in his last work, Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age (Harvard University Press, 2011). Here, Bellah shows us a brilliant mind, combing the sciences and the humanities for knowledge, accumulating insight over a lifetime. He marshals evidence from physical and cultural anthropology, evolutionary biology, archeology, social theory, musicology, and religious studies to argue for the deep evolutionary roots of the religious impulse in human life. Along the way, he demonstrates that religious commitment need not exist in tension with science, indeed that it can coexist with absolute commitment to the best science available at a given moment. I think Bellah sustained that combination seamlessly because his belief in ultimate truth fostered a confident insistence that the best science must in the end be consonant with the deep truths of the human condition. Some of the early reviews of Religion in Human Evolution simply miss the subtlety of insight there, so read it for yourself: Taken on its own terms, it rewards the careful reader with a framework for the sociological and non-reductionist study of religion. I am currently teaching it to my undergraduate students.

Bellah will be remembered for multiple contributions to human thought and democratic life. He helped us come to critical terms with our roles as scholars, institutional leaders, and democratic citizens in the long-term struggle to deepen democracy in America and around the world. He analytically proposed and personally lived out a framework for integrating faith and social science, not in a mode that sheltered faith from critical inquiry (from within or without), but rather in a mode that took science and faith radically on their own terms and trusted that deeper understanding would emerge from their juxtaposition. And he sought out the deep roots of religion qua symbolic thinking, groupness, ritual, and ultimate meaning; found those roots in the loam of human evolutionary history; and located that history within a cosmos open to scientific inquiry and the religious imagination.

Bellah liked to quote the great China scholar Herbert Fingarette: “One may be a sensitive and seasoned traveler, at ease in many places, but one must have a home.” In the end, I think Bob Bellah found his home in something like this idea: Only the symbolic truths carried in the great religious traditions are capable of providing the cultural meaning, the social solidarity, and the human formation needed if we are to sustain the long democratic struggle for the good society. He also found his home in one of those great world religions, but always remained a religious cosmopolitan open to inspiration and insight from any of them – and from secular thought. Thus, for Bellah religious commitment was no easy, self-satisfied stand, but rather a challenge to deeper engagement and fuller life.

In the shadow of Robert N. Bellah’s death, his thoughts on eternity may offer an appropriate way to illustrate the rich complexity of his stance in life. In a letter to his former student and friend Samuel Porter, Bellah wrote: “As for eternal life, that is now. If we don’t see eternity in a grain of sand, when will we ever see it? As for resurrection, as Tillich said, dead men don’t walk. But Christ was surely resurrected in the consciousness of his disciples and is more alive today than the day he was crucified, in the faces of all those who follow his example and who keep him alive. Many wonder workers have resurrected the dead. I never understood those who think the truth of Christianity hinges on the physical resurrection of Jesus. If that is the test, then a lot of nutty religions are also true. Eternal life is here and now. Christians have hardly come to a consensus on life after death. Augustine thought we would join the choir of angels in singing an eternal Hallelujah. Fine with me. But most Americans who believe in life after death think they will rejoin their dead family members and live happily ever after. A very modern, bourgeois kind of afterlife, hardly what traditional Christians thought. But I have no interest in destroying the beliefs of others. If thinking one will rejoin one’s loved ones helps bear the pain of death, then I’m all for it. I have to look elsewhere, and, with Heraclitus, declare that life and death are one.” -- In memory of Robert N. Bellah Richard L. Wood University of New Mexico